The more I think about it, the more preposterous and uncharacteristic it seems that Claude Debussy, that impressionist heavyweight champ, might cure my hangover on a Monday morning. I will not even pretend to know what compelled me to dig up this old 70s suggestion. Thanks, however, are due not entirely to good old Debussy but additionally to Japanese synthetist Isao Tomita, a man who has utterly transformed my appreciation for the incredible potential of a pre-Scott Joplin landscape, one dominated, I think I may say, in popular memory by music for orchestras. Listening to Tomita’s 1974 realization of Debussy’s “tone paintings,” arranged masterfully on MOOG synthesizers is a lot like what walking on another planet must sound like. The record in question is Snowflakes Are Dancing and Christ, it’s an absolute gem.

But first, a little backstory.

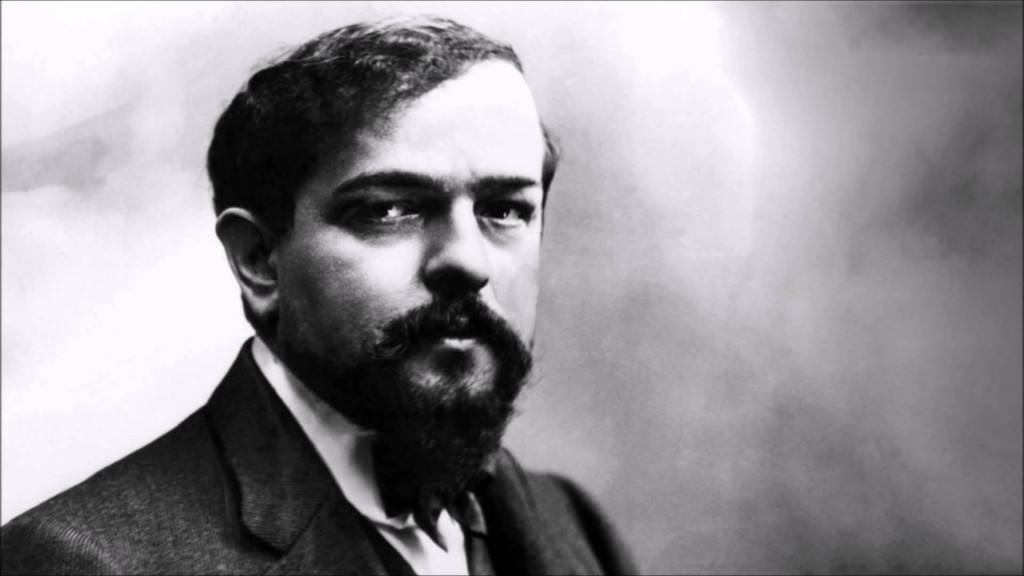

What can I hope to say with authority about Claude Debussy? Not a whole lot, I’m afraid. My knowledge spans little further than that of encyclopedia articles and conversations here and there, a travesty, I’m sure, in considering someone of such high regard. So it goes.

A French composer, Claude lived from 1862 to 1918 and managed to become one of the world’s most prominent artistic figures, pushing the boundaries of tonality (“the use of conventional keys and harmony as the basis of a musical composition”) so as to articulate heightened sensory detail and color, musically. Though he wrote and published many compositions throughout his life, “Snowflakes Are Dancing” primarily covers material published roughly between 1890 and 1910, material that has been said to reflect the ideologies and works of the impressionist and symbolist painters of the time. Such ideas, as I’ve come to understand, as not focusing on realism, and also as capturing light, the passage of time and other examples of transitoriness. So ends a millennial hack’s Debussy crashcourse.

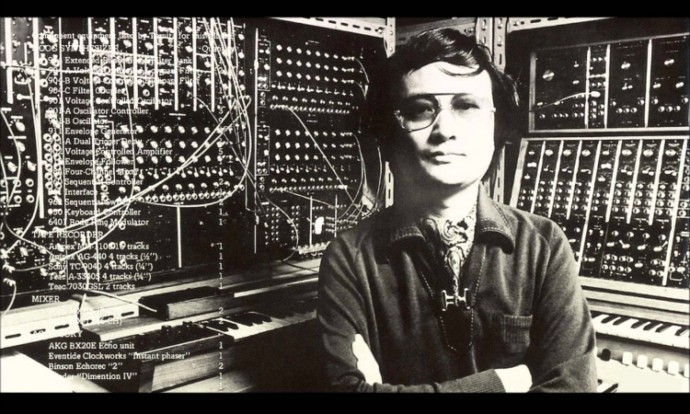

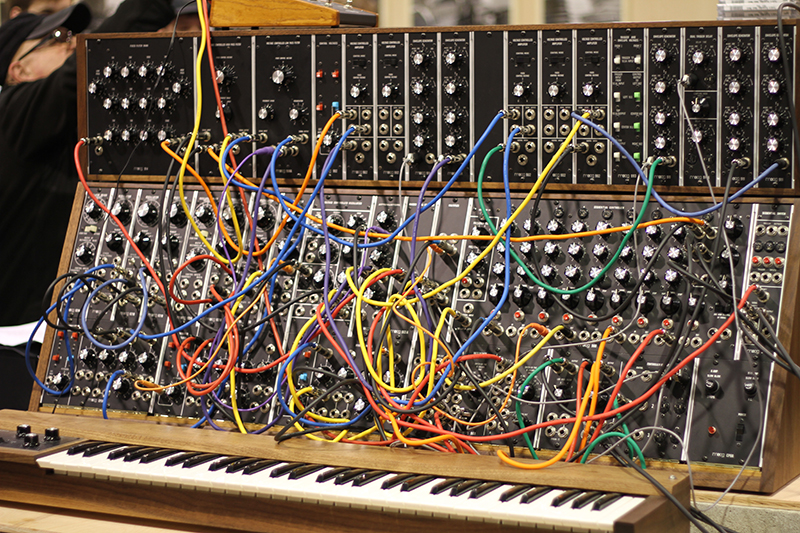

Enter: Isao Tomita, electronic music synthesis extraordinar born in 1932, that undeniable legend and pioneer responsible for the beautifully executed and yet no doubt mammoth note for note recreation in question. Anybody remotely familiar with the technically demanding and often unwieldy nature of the analog synthesizer equipment of the 1970s is bound to be awestruck by his meticulous and highly emotive electronic realizations. For those less familiar, merely seeing one of these machines is informative as to their operational complexity. These instruments are those of science fiction. Towering high above their operators, countless cables spilling from their endless ports, with hundreds, even thousands of knobs speckling their humming surfaces, they are the sort of thing you might expect to find in a Dexter’s Laboratory rather than in a studio. I mean, for christsakes, you’d be hard pressed to turn one of these babies on, let alone to create something so vigorous and human. Fourteen months well spent, Tomita. Fourteen months well spent, indeed.

But it’s hardly all roses, I’m pleased to report. Critic and contemporary Andre Suares said of his old friend Debussy: “He was an ironic and sensual figure, melancholy and voluptuous. … Highly strung, he was master of his nerves, though not of his emotions.” This too comes through with more force on Tomita’s realizations, which breath and swell in a far more lifelike fashion than their corseted acoustic brothers and sisters. This vitality allows room for a greater breadth of emotion, for abrupt yet seamless transitions to darker moments such as on “The Engulfed Cathedral” not to mention the damp, shrouded, sonic caverns of “Footprints in the Snow.” By contrast, “Clair de Lune, No. 3,” one of Debussy’s most famous and recognizable works (even for ignant scum such as myself), is just about the most hopeful and teleportive piece I know. The highs and the lows, sonically and emotionally, dude. They really do help to make this record a damn grand one.

“Snowflakes Are Dancing” manages to defy all expectations of the colloquially “classical” and is a record even those typically indifferent to such an experiment are likely to enjoy. To put it more bluntly, I think it’s a terrific piece of work and I think you’d benefit from giving it a listen. I’m not talking about the typical uppity background nonsense that we’re all too familiar with and that we’ve perhaps unfairly cloistered ourselves from. I’m talking about an enduring record, one that lives and breathes, one that demands your attention and frankly, deserves it. It is a cultural event and even perhaps an indicator of how hundreds of years of music might be made relevant and accessible once again. Maybe the music of the past does in fact have a future, or even just a shot at a more popular redemption. Maybe good ideas can be born of bad ones, like Sunday night drinking, for instance. Go fuckin’ figure.

good verrsion of clair de lune.