Writing about The Beach Boys is often a frustrating (or even upsetting) affair for a fan such as myself. Sure, they’ve had a helluva ride over the last fifty years, but to an extent they’ve been coasting, predominantly relying on their 60s surf-rock singles, the masterful Pet Sounds, and that relapse known as “Kokomo” to preserve their popular legacy. Maybe it didn’t have to be this way. Enter: Brian Wilson, our tragic hero, the musical auteur crushed under the weight of his extremely ambitious and until recently unfinished SMiLE, a record that began in 1966, meant as a friendly yet formidable answer to Sgt. Pepper’s.

My baby and I just want a good time

Might go up in smoke now but what do we care

My baby and I just want a good time

— Brian Wilson, Rolling Stone, March 1977

Given this context, it is nothing short of astounding that in 1976 Brian Wilson inexplicably, if only temporarily, reclaimed something within himself which allowed him the confidence to undertake what would be his most ambitious project in ten years: one that would ultimately prove to be the last truly great Beach Boys record, one almost entirely written, recorded, and produced by Brian Wilson, and one that would come to be known as The Beach Boys’ Love You. It is without question one of the most peculiar Beach Boys records one might hear, especially for those only well acquainted with the band’s surf-based stylings. Love You offers a rare, one-time-only sound, that of the innocent, optimistic, and naive cries of Brian Wilson, that then (and now) (mostly) hoarse man-child featuring the prominent backing of minimoog synthesizers.

I know what you may be thinking, a Beach Boys synth record? What the fuck? And yes, it is totally strange conceptually. I acknowledge this fact, dear friends, sweet, sweet limited readership of mine. But this record is no joke, believe you me and such is evident from the start, with “Let Us Go On This Way,” a commanding synth driven entry track including the delicate harmonies for which the band has been come to be known. One of the most interesting elements of this album has to do with the child-like naivety that permeates each track. But maybe that’s not quite it. “Man-child” is not an accidental (nor an original, I do not think) descriptor for Brian Wilson, especially in the context of Love You where it feels like he has reverted back to highschool. On “Roller Skating Child,” already questionable in title, the 35 year old Wilson sings to the song’s subject: we’ll make sweet lovin’ when the sun goes down/ We’ll even do more when your mama’s not around. And yet somehow this fails to be creepy. It may be corny to say but he just sounds so endearing – that’s the thing about Brian Wilson, he is perhaps the least cynical musician on the planet. He works in goodwill and sincerity and pretty much always has. What we see here is a man stuck in the past, perhaps one seeking refuge in the innocence of childhood as a means of relief while in the midst of rehabilitation. Then again, I am no doctor. That portion is mere speculation.

When you think about it, though, Brian Wilson has always been stuck in the past. The Beach Boys sound, primarily indebted to doo wop groups like The Four Freshmen and The Five Satins, had long since gone out of style by the late 50s and early 60s with the rise of guitar-based rock n roll. Moreover, their long enduring clean-cut appearance and ra ra “Be True To Your School” semi-patriotic mentality paired with ballads sweet enough to make Sinatra look a dirty old man made them the ideal parent-pleasing band, I’m sure. Though Brain and the boys were far from clean-cut in 1976, these defining yet dated-on-arrival Beach Boys qualities are present on Love You. “Mona,” for instance, is perhaps one of the most well meaning, wholesome, songs I’ve ever heard, with an upbeat Brian raspily crooning a dinner and drive-in type of love amidst a constant and repeated melody. The twist of the minimoog is sonically interesting throughout and was at the time, no doubt, cutting edge. However, listening back now, it too sounds dated, a bit like a gameboy, actually. This is not to the record’s discredit. You simply don’t hear synths like this anymore.

Love You starts off with upbeat, quicker songs and moves into a succession of tender ballads on the later half. Later tracks like “The Night Was So Young” and “I’ll Bet He’s Nice” are among the finest ballads Brian Wilson has ever penned — simple, gentle, and more than comparable alongside classics like “In My Room” and “Surfer Girl.” The ballads, in particular, are enhanced by the wonky sounding synths which successfully add a textural element previously foreign to the Beach Boys – a sort of “it’s so crazy it just might work” situation that does, in fact, pay off. There are outright weird tracks here too. “Johnny Carson,” a delightful homage though it is, marks one of the silliest songs in the extensive Beach Boys catalog and one I would kill to see The Roots perform with Jimmy Fallon today. Imagine: Who’s the man that we admire/Jimmy Fallon is a real live wire! Only “Ding Dang,” an erratic minute long track which Brian reportedly obsessed over, is deserving of skepticism. It is hard to know what he ever hoped to accomplish with such a song. Are we hearing the inner workings of Brian Wilson’s mind? It’s possible but again, it is hard to say.

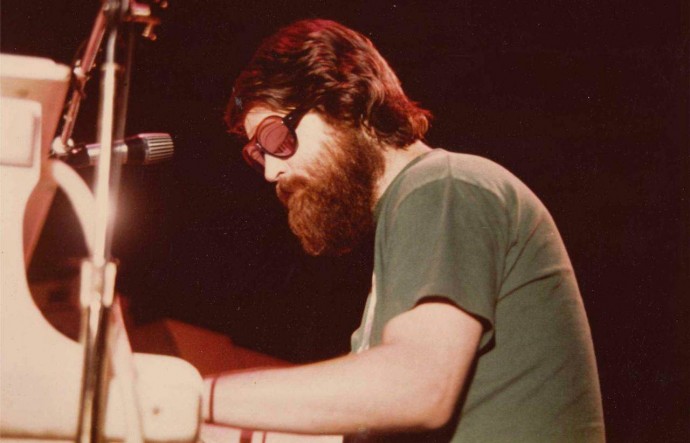

Brian Wilson sings Love is a Woman at SNL by dailyboo_

The Beach Boys Love You ends with “Love Is A Woman,” a track I have always found ominously reminiscent of a captain going down with his ship. Lyrically there is no justification for this imagery, the song is a fairly simplistic one, essentially instructing the listener to treat women “right” should he hope to find love. And yet there’s something in the music that feels unpleasantly final, like the sonic representation of that brief period of reclaimed sanity and musicianship coming to an end no sooner than it began. It’s the sort of song one might expect to find a washed-up drunk howling in some dark dive on a Sunday night or more fittingly perhaps, on a Monday morning. Sure, I’m probably projecting my knowledge as to Brian’s long enduring post-Love You hell onto the song. That would certainly be the logical explanation for my take. But when watching his 1976 SNL performance of “Love Is A Woman,” I can say for certain that I do not see a happy, stable man. I see an overweight, over-anxious, uncertain man-child, looking a lot more like 45 than 35. What I see makes me sad. Love You is the product of a mentally troubled and physically tormented young man grasping in the dark years and many trying trials before finding a suitable support system and learning once again to be sustainably happy. As such, whether you call it optimistic or call it delusional, this primarily ebullient synth-pop oddity in the Beach Boys catalog is both a personal triumph and a musical one for Brian Wilson. See that you lend it your ears, old sports. Over and out.