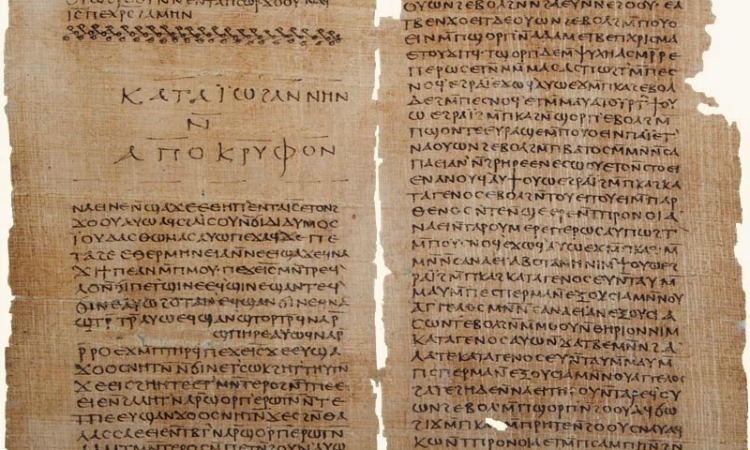

Workman Song is the solo recording project of one Sean McMahon, a 25-year-old Western Massachusetts native currently located in Brooklyn. I feel hesitant describing him because he’s penned far too many witty epithets for me to ignore (“Part ghost, part Victrolaphone, part campfire storyteller”; “scorpio seeks capricorn for ascent of mt. carmel / proficient bardic gospel storyteller w experience in srvc industry”), but I will comment that the notion of narrative is involved in nearly every self-description he has written. Moreover, this album isn’t even directly at Workman Song album, but an Ion Zelig one (who McMahon describes as a ‘sub-persona’ of the Workman Song persona) – there’s levels to this shit. McMahon describes the album not only as something which originated from five years of studying Gnostic codices and at least a month of mixing sound to be as weird as possible in the back of a tour van, but also as something which has made him happy (“in life, actually happy”). My job here is to deconstruct the chaotic-yet-cathartic process which led McMahon to such happiness, and perhaps your investigation, o reader, may begin with the juxtaposition of these lofty inspirational texts and the middle-finger album artwork. In the meantime, I’ll attempt to provide a brief summary of the multiple essays Sean sent me detailing the context of this album. First, his own words (greatly abbreviated/edited to please those with short attention spans):

Maybe I’m saying that Ion Zelig is my first protest record, and what it took to get me there is what led to my finding peace.

‘A very colorful alternative history of the world’ is a pretty concise and beautiful way to summarize this album, I’d say. The middle finger is growing ever more relevant; why accept the narrative we’ve been handed when we could create our own narratives? You should probably hit ‘play’ on the first track to gain some concrete audial memories of this album instead of just my interpretation.

“Soldier” is about choice: one can fight for truth, or one can become a digit of the beast described in the song (“a lethargic and anti-social creature whose innards communicate via wire-tapping and whose rent is very expensive”). The vocal delivery reminds me both of Ruban from Unknown Mortal Orchestra and Jeff Mangum of Neutral Milk Hotel, mixing folksy roots with elements of modern electronic production (reverb/delay/hard panning). The guitar tones are also weird enough to warrant a mention in this stylistic comparison, mixing crunchy electro tones with more drippy acoustic ringing. I’m not the kind of guy who finds himself compelled by vocal-driven music very often, but Workman Song is the kind of project where every lyric is important and the instrumental arrangements are set up in order to emphasize the narrative (which is, naturally, delivered by voice).

“Menorahs” is about the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah and the subsequent relocation of the royal line of Jerusalem to Ireland, where the power structure spirals downward because of “Empire stuff.” Vocal delivery is, of course, yet again on-point (“Jesus went to sodom with moses and elijah” is spurted out coyly over an extremely minimal yet compelling snap/clap beat); the 808-kit-style rhythm draws us slightly out of our comfortable folk-listening habits only in order to sit us down for an alternative folk tale. It’s a super unusual effect.

“When People Are Better Than You” is about love and friendship overcoming self-appointed authority (i.e. discarding hierarchy in favor of fraternity). The music video which accompanies it is one long shot of McMahon doing interpretive dance and shadow puppetry to his own music (mostly pelvic thrusting at the beginning) as the lyrics scroll by in bold, all-capital-letter text. The lyrics are arranged in an aesthetically appealing way (think Mallarmé, but maybe not sober Mallarmé), but the production value of the video is pretty low. This video, it seems, is the source of the album artwork; upon reflection, it makes a lot of sense that the imagery for a narrative should go no further than the narrator himself (and what he can describe in the story). The laser-gun guitar parts on this track are accompanied by a Dylan-esque grimy vocal melody, a never-ending verbal/melodic assault which comes across almost as a drone. If I was gonna make a comparison, I guess I’d say Kurt Vile, but it’s just fundamentally not the same artistic intention here. A happy accident of similarity, one might say.

“Sophia is Smiling” begins with a loop of what sounds like a keyboard-generated horn beep, but this is quickly drowned out by a filtered spoken-word part (“it took a lot of trying / but now i’m jacked in / the power source is pulsing / my life force intact”) hidden amid a haze of percussive clicks and unidentifiable looped clips which serve the function of synth pads (but which may be in actuality anything from a pitch-shifted vocal sample to something created completely from scratch on a synth). This is my favorite track of the six on Ion Zelig Vol III – it reminds me of Radiohead’s “Fitter Happier” in both its narrative function for the album and the sound collaging which disguises the narrative. Sean advises us that Sophia is the aeon, wisdom, which will redeem the chaos of the codices/of this album; I advise you to carefully read the lyrics lest you become completely dwarfed by the multiplicity of significances at play here. The track ends in abrupt horn loops and dreamy guitar parts which are mixed extremely intelligently, an expert conclusion to our visionary/out-of-body experience built neatly into the center of the album.

“Pockets” is literally a conversation between our narrator and God wherein the narrator reminds God that most people don’t believe in him anymore as a result of economic injustice (“you filled the pockets of the poor / he who had you gave him more”). This is probably one of the more accessible tidbits of sound on the album, but I think it would sound pretty 80s-pop instead of gnostic-folk if it was torn out of context (the bassline and melody are both played on keys, and most of the percussion is an open hi-hat and an artificial-sounding snare). “Veronica” is a portrait of the archetypical whore, the symbol of the true face of society’s collective desires. McMahon himself expresses some uncertainty as to why Veronica fits as the last song – I don’t think the narrative necessarily needs a solid conclusion, especially if this is merely an episode in the Ion Zelig saga. Musically, the closing track is everything I wanted it to be; open guitar chords and throaty folk singing in the style of Daniel Rossen lull your possibly Judeo-Christian worries into submission as the last notes of the EP play out (“do you love me? do you love”).

My closing comment about this album is that I hope that people can feel comfortable replacing their idea of an elder sitting by the fireside with that of one Workman Song – McMahon has proven that he is not only capable of telling better stories than your grandaddy, but also capable of telling them with musical accompaniment.

You can juxtapose my review with Sean’s self-review, if you like. There isn’t much room to form personal interpretations when there’s such rich contextual information and already-present artistic interpretation of historical texts at play here – why bother trying to make broad statements about artistic intent when we’ve received such specific instructions as to how we should interpret the text from the artist himself? These aren’t hints, these are interpretive commands. And I don’t say this in a disparaging way, but rather from a viewpoint of one who has been pleasantly surprised; from a critical perspective, it is wonderful to (for once) not have to propose a theory of the album’s narrative but rather to simply synthesize what the artist has given me in text and in sound (plus my own experience in listening, obviously). There’s a joke to be made here about alternative music and culture versus alternative Biblical interpretations, but clearly I lack the delicacy of phrasing to formulate it properly at this point. I’ll give the mic to Sean yet again for his self-review (which you can see for yourself in full detail on his bandcamp!).

“When People Are Better Than You” and “Pockets” are the most important songs of this release.

I should have explained earlier that Ion Zelig is a character that comes to mind (whom, I guess, I inhabit) when I write experimental music, particularly electronic. He is probably half-robot, a Martian scientist, and all that. He is a bit spindly and weird, but benevolent. This, actually, really is the third volume of Ion Zelig experiments I’ve published, it’s not just a clever name. I can’t remember where the other two volumes are located. Somewhere on the internet. Probably listed under “Sean McMahon.”

Anyway, I meant to close.

Enjoy the sermon that is “Sophia Is Smiling.” That one will take me a long time to figure out, but it grows on me. Similarly, you will ask yourself at the end of this EP, “Why ‘Veronica’?” I’m there with you.