-Paul Nelson, Rolling Stone, “The Crack Up and Resurrection of Warren Zevon”

If you’re anything like me, you approach the vast majority of live records with a hearty dose of skepticism, almost inherently suspicious as to whether or not the final product warrants serious consideration alongside an artist’s studio recordings. This skepticism doubles when considering the case of a lesser known artist as such live performance records often offer little to the newcomer, serving primarily as supplementary material warmly welcomed by die-hard fans. Simply put, the very nature of such insider releases rarely proves conducive to a successful artistic introduction. With that said, old sport, we’ve likely all had one such record pushed upon us at some point or another by a well meaning friend who’s just a little too enthusiastic about its supposed nuances – the deadhead carting around a hard drive with like thirty days of live jams comes to mind. Hell, I come to mind at times. But there are examples of when a live record can genuinely exceed expectations, triggering a profound interest in an artist in such a way that conventional studio recordings simply cannot.

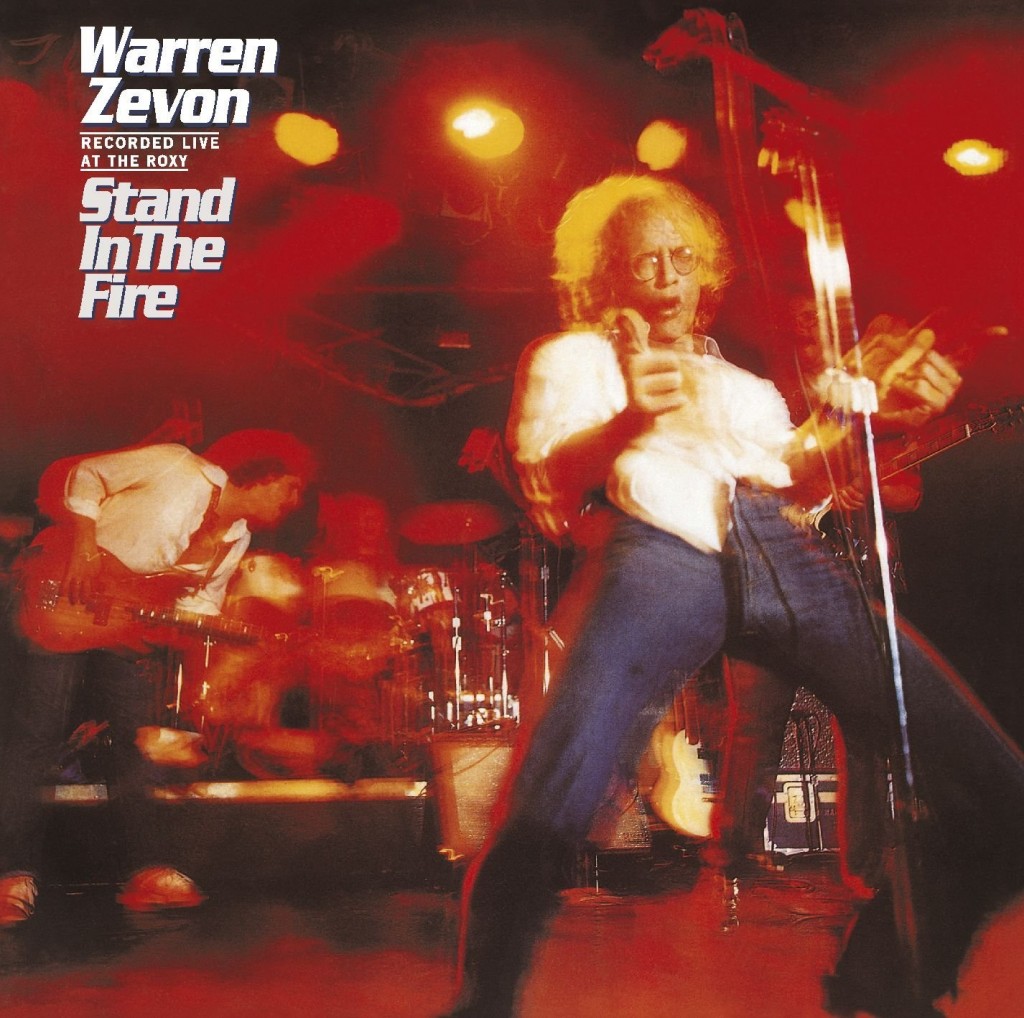

Stop Making Sense by the Talking Heads serves as a prime example, sonically exhibiting not only Byrne’s distinctively odd mannerisms but also displaying his band’s quirky creativity, ability for improvisation, and formidable capability as live performers while simultaneously championing their broad musical stylings via a set list that covers the group’s catalog defining tracks up to that point. The well-recorded nature of Stop Making Sense on the whole allows for one to focus on the delightful details for as one is intimately introduced to the group’s personality, the added and undistracted personal texturing yields an improvement on almost every studio original by virtue of the listener’s improved understanding of the men and women behind the music. I mean, really, what could be more quintessentially Talking Heads than the extended, stumbling outro on “Psycho Killer,” not to mention Byrne’s typically awkward introduction at the track’s start. But I’m not here to talk about David Byrne or the Talking Heads. Instead, I write on behalf of a gunslinging, excitable boy who would come to be known as “Mr. Bad Example,” a hard living artist who accurately and hilariously stated “I got to be Jim Morrison a lot longer than he did.” Ladies and gentlemen, I am proud to present Warren Zevon and his phenomenal 1980 live release, Stand In The Fire, a career defining and near perfect rock & roll artifact which demands the attention of any true friend of the genre.

But who is Warren Zevon? If you’re at all familiar with his work or even if you’re not for that matter, you’ve likely heard “Werewolves Of London,” by far his biggest commercial hit and one that has effectively and unfortunately eclipsed his career. “Werewolves Of London” is to Warren Zevon as “Come On Eileen” is to Dexy’s Midnight Runners: both are terrific pop songs representative both of each respective artist’s musical style and personal flair but over time, both have distracted and drawn focus away from the wealth of additional worthwhile material they each possess. Born in Chicago in 1947, Warren Zevon’s winding musical path would see him through a number of phases before he’d achieve modest commercial success as a solo artist with the release of his critically acclaimed 1976 self-titled true debut. There was his stint as a psychedelic folk singer in the duo lyme and cybil for instance, and his many years as a songwriter for the likes of The Turtles and Linda Ronstadt among others. He wrote songs for commercials and films like “She Quit Me” for 1969’s iconic Midnight Cowboy. He even served as the musical director for The Everly Brothers’ touring band for a time, forming close and lasting relationships with the then feuding pair in the process.

Through it all, however, his early years and even the latter ones, Zevon’s work consistently earned him the respect and support of figures far more famous and influential than he. Take, for example, Jackson Browne, that dreamy 70s singer-songwriter who not only spent years flexing his commercial muscle as a means of effectively forcing Asylum to sign Zevon but who then also produced his first two records, leveraging Zevon’s powerful work to marshal a cast of eager and willing all star musicians to contribute to the highly polished studio recordings. The notable collaborators on 1976’s Warren Zevon speak for themselves: Jackson Browne, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks of Fleetwood Mac, Glenn Frey and Don Henley of The Eagles, Carl Wilson of The Beach Boys, Bonnie Raitt, Phil Everly, and Waddy Wachtel to name a few.

Thematically speaking, Zevon’s work both musically and lyrically proves deeply rooted in the masculine mythology of Americana. An infatuation with national cultural facets such as the wild west, film noir, pulp fiction, and contemporary folkloric figures partially pinpoints the origin of his tendency to glorify machismo. But if he sometimes comes off as one emptily touting archetypal masculine cliches, it is at least partially a result of his upbringing, one seemingly straight from fiction with his little present, hard drinking, bookie, gambler, gangster father, William “Stumpy” Zevon, a close associate of notorious LA mobster Mickey Cohen, to prove it, even once telling his son that “Al Capone was a good man.” But Zevon also willingly played the part, enthralled with the writings of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, intrigued by legendary western outlaws like Jesse James, wholeheartedly in love with cars, and, often irresponsibly, head-over-heels in love with firearms, too. In one instance, in the midst of one his unfathomable, marathon-like benders, he demonically fired several rounds from his .44 Magnum over the Sunset Boulevard at a billboard of Richard Pryor from the comfort of his suite in Los Angeles’ swanky Chateau Marmont after possibly having an affair with Bianca Jagger. Yeah, Mick’s wife. Such bad behavior, once undeniably linked to popular perceptions of rock & roll, simply wouldn’t fly today. This much is obvious.

But there’s another side to Zevon’s coin and, given his prevalent, well documented antics, it’s understandably tough to imagine a thirteen year old Zevon not only eagerly studying classical music, but doing so, if only briefly, under the instruction of renowned composers Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, managing to impress the pair in the process as well. Such sheds light on why throughout much of his career Zevon would toil on an ultimately unfinished symphony. “Bob Dylan invented my job,” says Zevon on David Letterman in 1987. Asked to elaborate, he continues: “I applied for the job of folksinger, spokesman for my generation.” His ambition was symphonic, grandiose by nature.

-Robert Craft, excerpted from his original typescript entitled “My Recollections of Warren Zevon”

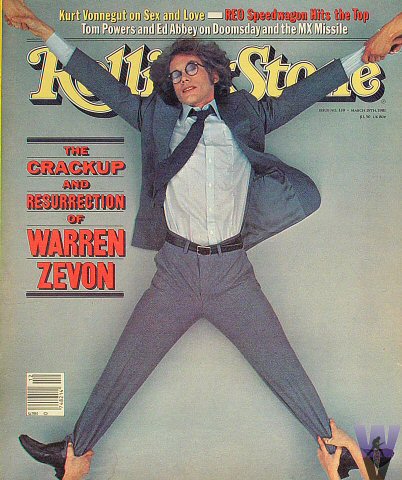

But by the late 70s, the already hard-drinking Zevon began to lose control, pushing his drinking and drug use to new heights at the cost of harming loved ones, alienating friends, a helluva lot of trouble with the law, and risking his very life as well. Though such had been escalating for a while, flirtations with mainstream commercial success by way of his critically acclaimed 1978 sophomore effort, Excitable Boy, featuring the aforementioned hit single “Werewolves of London,” encouraged neither sanity nor sobriety from our vodka guzzling outlaw. In his essential and intimate, forty-plus page Rolling Stone cover story titled The Crack Up and Resurrection of Warren Zevon: How He Saved Himself from a Coward’s Death, renowned music critic Paul Nelson, one who would personally participate in and write on his friend’s intervention, recalls a call from a devastated Crystal Zevon, Warren’s wife: “He’s dying, Paul. Some days, he can’t even dress himself.” Things were bad. Real bad. And were it not for Crystal, Warren Zevon would reportedly have never made it out alive. Of her say at Zevon’s intervention, Nelson recalls: “An hour later, I felt that I’d led a very sheltered life; that I’d just been pulled through every nightmare sequence a spiritual terrorist like Ingmar Bergman could dream up; that The Lost Weekend was nothing more than a pleasant little fairy tale for children; that, were it not for his wife, Warren Zevon would have been dead ten times over; that – if there were still saints in this world – I’d just been listening to one.”

So Zevon, our leading man and far west Hollywood hero fought the good fight and finally got sober, dedicating the entirety of his newfound clarity and renewed focus to his third record, Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School, released to critical acclaim in 1980. On the record’s subsequent “The Dog Ate The Part We Didn’t Like Tour,” featuring his long time friend David Landau on guitar with Boulder (an unknown Colorado band) to back him, Zevon reportedly exhibited his musical and performative peak, having apparently shed his vices with no loss of that intense savagery or his beloved, morbid wit. This is the part of the piece where we finally find ourselves equipped to discuss the live album in question, old sport, 1980’s Stand In The Fire, recorded towards the end of the Bad Luck tour over the course of a five day residency at the Sunset Strip’s intimate Roxy Theater.

Dedicated to Martin Scorsese, Stand In The Fire is appropriately cinematic in feel, with Warren Zevon playing his most hard-hitting, gunslinging excitable self to date. Hell, it’s an Oscar-worthy performance with nothing held back, a perfect demonstration of what an artist might achieve through a continued, savage dedication to well worn cultural concepts within the context of a well defined musical mark. Leading off with its then previously unreleased title track, Stand In The Fire works into a frenzy, with the record’s contextually slow start and ensuing rapid rise reminiscent of an airplane’s ascent as it moves from the tarmac to cruising altitude. Not surprisingly, Zevon’s idea of cruising differs significantly from that of the average werewolf, evocative instead of a full on sprint rather than the leisurely pace suggested by the word “cruise.” While the first two tracks are worthwhile (Springsteen co-wrote “Jenny Needs A Shooter”), the characteristic high-octane mad dash begins with track three, namely, “Excitable Boy.” A personal favorite, it’s a vicious, catchy, and a hysterically dark improvement on the Beatles’ murderous yet by comparison fairly tame “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” Extended from the studio original by over a minute and a half, the song prominently displays the tightness of Zevon and his touring band complete with Zevon’s infectiously melodic pop piano work and two phenomenal guitar solos from David Landau. I get a little excitable just thinking about it.

“Excitable Boy” marks the true beginning of one of the finest rock & roll sets around and, with “The Sin” serving as the only slightly substandard exception, each and every track knocks it out of the park, revealing Zevon’s sincere intensity, his playful, grim satisfaction, and his lightning, ad-libbing wit. On “Mohammed’s Radio,” Zevon changes the original lyric from “You know the sheriff’s got his problems too / He will surely take them out on you” to “Ayatollah’s got his problems too / Even Jimmy Carter’s got the highway blues,” providing additional cultural context to the rockin’ ballad in his typical tongue and cheek manner. “Werewolves of London,” like much of Zevon’s work completely unneutered for the first time on record, chugs onward with a ferociously fun yet feral deliberation that’s all but nonexistent on the well-known studio original. Here, Zevon adds verses, changes lyrics, and comically inserts such cultural figures into the mix as Brian De Palma, James Taylor, and Jackson Browne. Though it’s possible that Zevon prepared such changes prior to the show – he would, for instance, write and practice jokes to tell orchestras in the studio so they’d loosen up and play better on recordings – it all feels completely off the cuff here with the following verse serving as my personal favorite addition:

It was a blood red Coupe de Ville

He said he was a drivin’ it to Mexico

Going down to Tiajuana

Gonna kill somebody in a film or something

“Lawyers, Guns and Money” is slightly slower here than originally on record, but surprisingly, I’ll admit that the benefit of its swagger and bravado is the sort of song one might walk (no, strut) on stage to, eliciting, no doubt, a standing ovation from the crowd. With a bouncy, memorable, and powerful riff to back it, the track boasts lyrics fitting and reminiscent of the sort of thing one might expect from Hunter S. Thompson in his Rum Diary days: it’s the story of a trip to Central America gone wrong with gambling in Havana, hiding in Honduras, and the frantic evasion of Russian spies, one on which you can almost hear a paranoid and debaucherous Thompson drunkenly screaming along. I went home with a waitress the way I always do / How was I to know she was with the Russians, too? Hah! In a lot of ways, Zevon may be considered the Hunter S. Thompson of rock & roll and, not surprisingly, the two would ultimately become close friends, sharing a mutual affinity for gunplay and literature as well as a mutual admiration for each other’s work and antics. “Lawyers” leads into “The Sin” which, though a fine track, is perhaps the record’s only non-essential cut. Next comes “Poor, Poor Pitiful Me,” a southern tinged dance rocker and another personal favorite from his self-titled debut, one that benefits tremendously here from the unfettered nature of his focused and hard hitting live performance. In but another hysterical and characteristic move, midway through the track Zevon pulls George Gruel, his then “road manager and best friend” up on stage to help rile up the crowd. George does his part, gleefully growling into the microphone: “Get up and dance, or I’ll kill ya! And I’ve got the means!” It ain’t that hard to see why the two got along.

And the good times keep on coming, with the semi-autobiographical “I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead,” a sort of hyper masculine, drug induced troop featuring a now fittingly and delightfully growling Zevon, leading straight into the record’s only cover, “Bo Diddley’s A Gunslinger” (can you guess who it’s by?), a well executed and completely appropriate choice given his thematic infatuations and musical tastes. The former foot stomper is so amazingly forceful it makes its original studio recording sound like soft rock and the latter, with its absurd subject matter, “George of the Jungle” drums, and irreverent, almost personified guitar, transforms the dated original into a driving Zevon classic. While on the original 1980 release, this is where the Stand In The Fire ends, the 2007 Asylum/Rhino remastered reissue includes four additional tracks so good that their initial exclusion feels both misguided and inexplicably baffling.

The first two of these four previously unincluded tracks are consistent with the hard rocking plateau reached and subsequently maintained by Zevon and the boys from the start of “Excitable Boy” to Stand In The Fire’s final numbers. “Johnny Starts Up The Band,” an extremely well crafted and satisfying song to begin with, exhibits some of the tightest playing on the record, with another bout of tremendous solo guitar work from David Landau, prefaced, of course, by Zevon howling “Heeeere’s Johnny!” on at least one account. The follow up, “Play It All Night Long,” with its surprisingly well aged western-style synthetic string melody and drums reminiscent of a military parade, proves another excellent addition, explicitly paying homage to “Sweet Home Alabama” and the struggles that come with living down home. Sweet Home Alabama / Sing that dead band’s song / Turn those speakers up full blast / Play it all night long. Moreover, Zevon’s effortless inclusion of a word like “brucellosis” later in the track serves as but another reminder of his top-flite lyrical abilities.

-Zevon, Play It All Night Long

The latter two previously unincluded tracks and final two on Stand In The Fire mark the jet plane Zevon’s final descent, taking things down several notches first with his superb, Aaron Copland-esque debut album opener, “Frank and Jesse James.” At this point hoarse beyond belief, Zevon performs his wild western outlaw epic all by his lonesome, accompanying himself on piano. Only here does one begin to get the sense of just how intimate Zevon’s performances at The Roxy were, with the crowd encouragingly clapping along in unison to what is, relative to the rest of the set, a completely stripped down performance, happily transporting listeners such as myself to little saloons many miles away and long since gone. These shows were important to the newly sober Zevon and while such can clearly be heard throughout the record, the last two tracks exhibit his mentality most audibly. Such is confirmed by Zevon’s poetic remarks to Paul Nelson regarding the record in question: “Let’s just say that it was like rescuing the little boy who’d fallen through the ice… Rescuing him while the whole world was watching.”

“Hasten Down The Wind” marks the record’s final track with a heartfelt and moving speech delivered by Zevon to the audience before playing himself out:

-Zevon

Covered first by Linda Ronstadt on Jackson Browne’s suggestion for her 1976 album of the same name, the track stands as one of the most mournful works of Zevon’s career. Because of its somber tempo, delicate piano, and focus on a relationship coming to an end, “Hasten Down The Wind” makes a lot of sense as the finale, a perfect and pretty place to part with his highly supportive and responsive audience. After the first chorus, the clearly quite emotional Zevon asks the PA to “turn up the house lights,” continuing to say in reference to the audience, “I found the ones who are my friends.” The crowd yips, yells, whistles, and applauds and the warmth and mutual appreciation brewing in The Roxy can be heard. Even years later and miles away, this conclusion is bound to elicit an emotional reaction from listeners everywhere. Maybe this is because it’s a beautiful, atypically vulnerable display from such an often otherwise hypermasculine, witty artist on the offensive. It operates ostensibly the same way that watching a cowboy riding into the sunset does visually at the end of a western, one bound to the road and unable to stick around, inspiring simultaneously feelings of happiness, longing, love, and heartache. I can think of no more appropriate an exit for Zevon, our tragic hero, that desperado under the eaves.

Though sober at the time of Stand In The Fire, Zevon’s troubles with drugs and alcohol would return, leading to some of the darkest, most debt-ridden, and least productive periods of his life. There would be many “comebacks” throughout his career with 1987’s Sentimental Hygiene, featuring backing from the then little known R.E.M., ultimately proving to be his last truly great work as a whole. I owe legendary music critic and personal hero Paul Nelson credit for exposing me to Zevon by way of his aforementioned Rolling Stone cover story, The Crack Up and Resurrection of Warren Zevon: How He Saved Himself from a Coward’s Death, an essential read for anyone further interested in Zevon’s complex character. I would also suggest Crystal Zevon’s biography, I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead: The Dirty Life and Times of Warren Zevon, consisting of hours of interviews from people close to Zevon in different periods throughout his life. More often than is flattering, I warn you now, his details ain’t that pretty at all.

In 2002, Zevon was diagnosed with inoperable peritoneal mesothelioma, a form of cancer. Given only months to live, he wrote and recorded one last star-studded record titled The Wind, appeared solo on The Late Show with David Letterman as the main event for one last time (he would appear on his close friend’s shows over 39 times throughout his career), and filmed a VH1 documentary, outlasting his life expectancy by several months before ultimately passing away on September 7th, 2003. On his last Letterman appearance, when asked if he knew anything that Letterman didn’t about life in the face of death, Zevon modestly and poetically replied “Not unless I know how much, how much you’re supposed to enjoy every sandwich.” Vonnegut would be proud.

Though Warren Zevon never became the sort of major star that he hoped to or was expected to be, the disproportionately significant starpower making up his devoted cult following forces one to question what the mainstream was thinking. How did so many people missed such an irresistible, literary, and excitable musician? Scorsese was a major fan, so was Johnny Depp and Clint Eastwood and Billy Bob Thornton was a close personal friend. Hunter S. Thompson and Zevon were close friends, too. Not to mention friends and admirers Paul Shaffer and David Letterman, with Zevon once calling the latter “the best friend my music has ever had.” Then there are the aforementioned musicians; Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne, Lindsey Buckingham, Stevie Nicks, Glenn Frey, Don Henley, Bonnie Raitt, Don and Phil Everly, R.E.M., and Waddy Wachtel, all of whom were close with Zevon. Typically, I’m not one for name dropping and I believe firmly that Zevon’s catalog speaks for itself but I do so here to illustrate the absurdity of how a man with so much talent, so much support, and the music to back it never got bigger than “Werewolves of London.” Stand In The Fire speaks further to this absurdity, demonstrating that when push comes shove, Warren Zevon, that rockin’ and a rollin’ literary outlaw rooted in the masculine folklore and mythology of americana could not only play it all night long but do so with the best of em’. Over and out.

P.S. – Please enjoy this list, a selection of my favorite Zevon tracks not mentioned above:

“The Rosarita Beach Cafe”

“The French Inhaler”

“Desperados Under The Eaves”

“Roland The Headless Thompson Gunner” (last track he performed live)

“Boom Boom Mancini”

“Reconsider Me”

“Splendid Isolation”

“Keep Me In Your Heart” (last track he recorded)

Lifelong Zevon fan here. Great Article! In 1995 I moved from Columbus, Ohio to LA chasing a comedy career. On that long drive I played Zevon’s 1976 “debut” repeatedly for inspiration. My first night in town I performed at the Comedy Store on Sunset and stayed at the Days Inn across the street being that I could not afford the Hyatt/”Riot House” or Chateau Marmont. The next day, I found an apartment in West Hollywood only a few blocks away.

Later that week, I’m in the building’s laundry room and chatting with a fellow resident. I mention that I just moved from Ohio and she asks,”With all the riot’s, mudslides and earthquakes why would you move here?” To which I responded, “Well, to quote Warren Zevon, “If California slides into the ocean like the mystics and statistics say it will, I predict this motel will be standing until I pay my bill.” She pauses for a moment and says,”Warren Zevon, huh?”. I say, “Yeah, have you heard of him.” She says,”Yeah, he lives on the third floor.”

So, for the next several weeks I was trying to “accidentally” run into my neighbor. Eventually, I did…..and made a total ass of myself. Sure, there were some relatively pleasant exchanges on occasion but for the most part I was like that Chris Farley character on SNL anytime I ran into the poor guy. I will not go into the sordid details of how I was possibly the most annoying fan of all time…..or how I almost got into a fight at the House of Blues with one of Zevon’s good friend’s….. or how I inadvertently insulted him while sitting in the sauna. I’m not going to tell you those stories because I’m saving it for MY book!

Long live Zevon and his fans. Keep him in your heart.

P.S.: Now that Cheap Trick is in…”Why Isn’t Warren Zevon In the R&RHOF?”

Maybe it’s late, but thanks for a nice pick-me-up. These songs have been a perennial fixture in my life too, and it always warms my bitter heart to see such well-written appreciation for the man and his music. Well done.

I’d quibble only with your choice of his last great album. In my book his greatest all-time masterpieces have to be the self-titled debut-for-all-purposes, Mr. Bad Example and Life’ll Kill Ya.