This article is the first by our guest contributor Cora Hollema, who recently published a book which you can order on her website. It’s a limited edition printing (just 500 books!), so don’t miss out on this exclusive opportunity!

Self-portrait, 1888

Oil on canvas, 129 x 88 cm

Collection of the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy

View full size

The seemingly effortless brilliance with which she turned out elegant (and sometimes flattering) likenesses of her wealthy clients earned Schwartze much success, but also harsh criticism, especially from advocates for democratization and the renewal of society and art.

Her active role in public life, including a range of official administrative and cultural positions, and the high prices she was able to negotiate, also provoked resentment. Even so, she continued to be much in demand as the leading portraitist of the Dutch elite until her death in 1918.

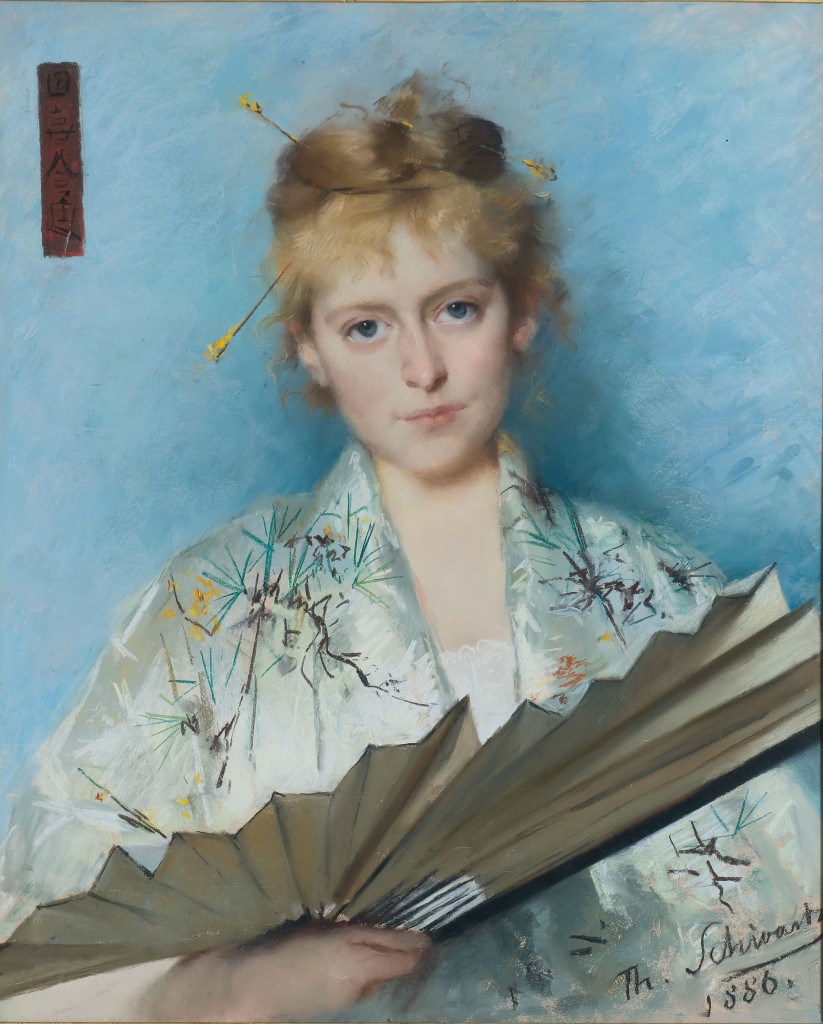

Portrait of Maria Catharina Ursula (Mia) Cuypers, 1886. (daughter of Pierre Cuypers architect of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

Pastel on paper, 71 x 56 cm

Private collection

Photo: Thijs Quispel

Woman wearing a hat

Portrait of Theresia Ansingh (Sorella), n.d. (after 1906).

Pastel on paper, 71 x 57 cm.

Private collection, Photograph: Thijs Quispel

View full sized.

This description of Schwartze’s character was made by her friend, the painter Wally Moes (1856-1918). In her autobiography, Moes dwells at length on her friendship with Thérèse Schwartze, who was five years her senior. The two had met in 1880, and Wally was astonished by Thérèse’s audacity and purposefulness. Moes writes:

“Schwartze had already built up a considerable reputation, could scarcely cope with all the portrait commissions that came her way, and was in a position to charge the top prices for her work. Yet she did not talk to me in the manner of the successful artist addressing a beginner; she treated me entirely as her equal, which both pleased me and made me feel a little awkward.”

In 1884 the two women spent four months together in Paris, to paint, to exhibit their work at the annual Salon, and to do some astute ‘networking’ on the art scene. The aim was professional advancement, and time was never wasted. Indeed, on one visit Thérèse used a moment of inattentiveness on the part of their host to ensure that they would not be late for another important visit. “On impulse, without giving the matter a second thought, Thérèse swiftly crossed the room to the mantelpiece and put the clock an hour forward. Great astonishment on the part of the host, and profuse apologies for being so late,” says Moes.

Their days were crammed with appointments, and it was generally Thérèse who took the initiative: “Indeed, I could not have kept up such a busy life for very long. Thérèse’s resilience, vigour and zestful spirit carried me along,” recalls Wally Moes.

The ‘American element’, with its un-Dutch audacity and grand scale that Wally Moes found so striking, was part of Schwartze’s natural heritage. Her family background was a history of migrants who succeeded again and again in building up new lives in the Netherlands, the United States, and Germany. They were cosmopolitans and knew how to adapt to – and take advantage of – new conditions, and to cope with the inevitable ups and downs. Vision, daring and perseverance are essential characteristics in these circumstances – as well as self-confidence, of course, a firm belief in one’s own abilities.

Portrait of Salomon Benjamin Druif, 1912

Pastel on paper, 55 x 80 cm

Private collection, Photograph: Thijs Quispel

View full size

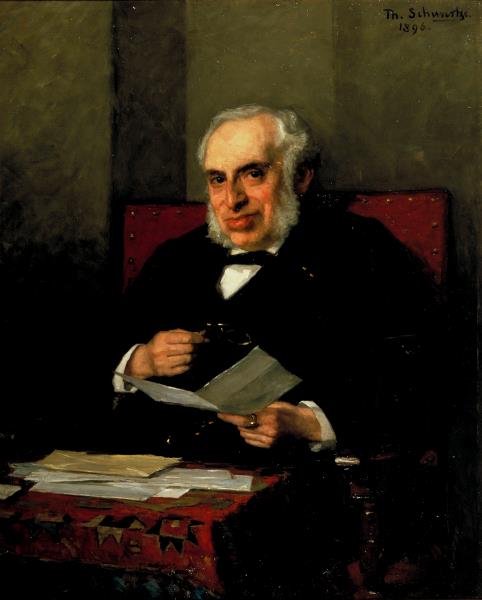

Portrait of Abraham Carel Wertheim, 1896

Oil on canvas, 103 x 83.5 cm.

Collection of the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam

View full size

In Philadelphia, which was then a booming city, Johann Engelbert Schwartze set up business as a merchant and chemist at several addresses in the city centre. His son John Theophilus Gottlieb Schwartze (1817-1877), one of Thérèse’s paternal uncles, ran a porcelain factory from 1852 to 1859 under the name of Kurlbaum & Schwartz, a brand that would come to stand for superior quality. The beautifully-decorated tableware produced by Kurlbaum & Schwartz can still be found today in museums such as Philadelphia Museum of Art. Kurlbaum and Schwartze were brothers-in-law: Charles Kurlbaum (1792-1875) emigrated to the United States in 1819 together with the Schwartze family and married his business partner’s sister, Clara Anna Maria Schwartze (b. 1812, Amsterdam).

Thérèse Schwartze’s father, Johann Georg Schwartze (1814-1874), was destined – as the eldest son – to join the business, but his passion was for painting. In Philadelphia he took lessons from the German-born history painter Emanuel Leutze (1816-1868), who had also emigrated to America as a toddler and who would later achieve fame with his patriotic painting Washington crossing the Delaware (1850). Painting was practised at a higher standard in Europe than in the United States at this time, and in 1838, at the age of twenty-four, Schwartze left for Germany to continue his painting studies at the Academy of Art in Düsseldorf. It was there that he met his future wife, Elise Herrmann, the sister of a fellow student, who would be Thérèse Schwartze’s mother.

Johann Georg raised his talented daughter Thérèse to be a breadwinner, in an age in which such an attitude to girls’ upbringing was exceptional. In the style of an obsessive ‘tennis father’, he drilled her in the essentials of painting from the age of five. In 1867 she wrote him a birthday card in which she promised to try even harder than before, so as “to be able to earn my living by painting”. This attitude is striking in its historical context: the idea of middle-class women earning a living continued to be taboo throughout the nineteenth century. Thérèse more than lived up to her promise, becoming the most successful and best-paid society portraitist of the Netherlands in the nineteenth century.

Self-portrait with black hat and glasses, 1917

Pastel on paper, 55 cm x 47 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

View full size

The motives of Thérèse’s father can best be understood in the context of his own background as a migrant and his cosmopolitan life history. He had an ingrained understanding that life may always take a sudden turn for the worse, in financial and other respects. He and his family had personal experience of such reverses. Emergencies may always arise that need to be anticipated as pragmatically as possible and overcome, but unexpected opportunities may also arise, which can be seized in ways that assure success. Such a life calls for courage, unconventionality, a businesslike and vigorous approach, discipline, flexibility, charm, humour, optimism and belief in one’s own talents. To a large extent, these qualities also seem to have determined the character and brilliant career of Thérèse Schwartze. Characteristics that are probably more likely to develop in circles of migrants and businesspeople than in more conventional milieus. In such respects, the United States acted as a frame of reference: it was a land of unlimited possibilities, free from the conventions associated with the ‘Old World’, including those relating to the position of women.

Wally Moes saw this influence in her companion: Thérèse’s energy and her fierce instinct for survival could have guaranteed success in whatever profession she had chosen, wherever she had pursued it. “Thérèse has not a grain of that quasi-artistic, limp self-indulgence… She automatically keeps herself at full stretch as long as it is time to work; she never gives up, and can’t see any benefit to be gained from listening to the sound of her own voice and analyzing her own feelings in vacuous self-pity… she never wastes an opportunity to exploit her talents to the full, or to strengthen her position and calling as a portrait painter… If painting had not been in her blood, she would have undertaken something else and made a success of it with the same conviction and passion.